Obviously, many of the idioms popular in everyday speech come from our roots as an agrarian society. People who have never seen or raised chickens casually comment on counting them before hatching or what they’re like when decapitated.

I, too, have used farm sayings all my life, even when I lived in a highrise in the middle of a city. However, now that we have moved to a small urban farm, I have a whole new appreciation for these common turns of phrase.

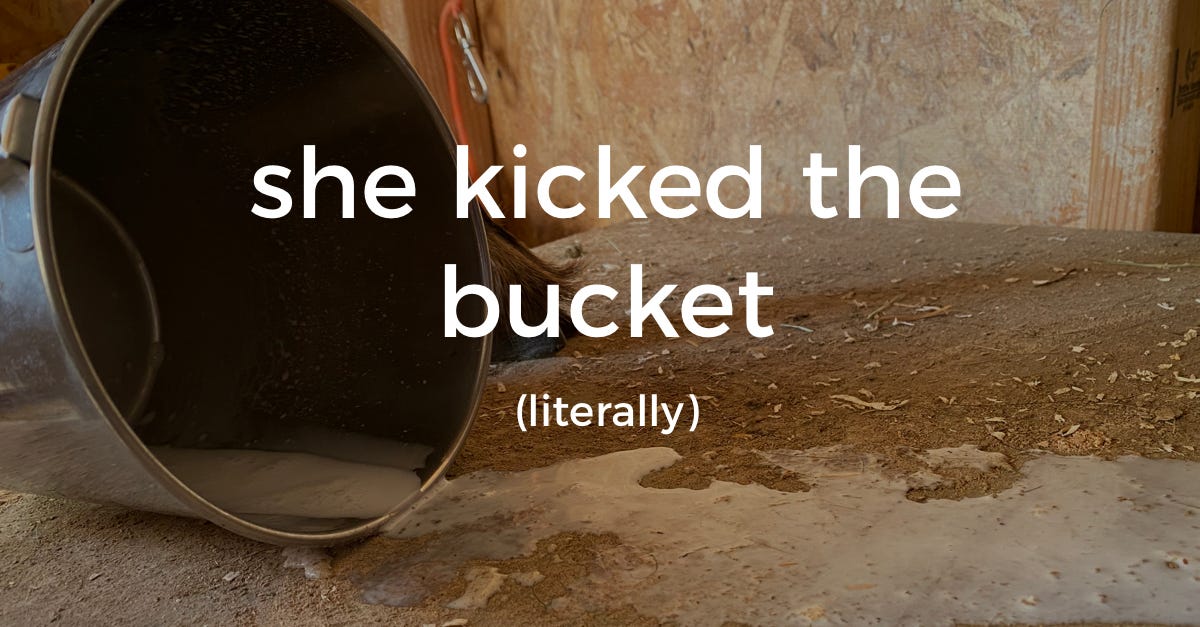

Kicked the bucket

There’s the literal “kicked the bucket,” as in a foot met a receptacle, and then there’s the figurative “kicked the bucket,” as in somebody died. I always thought it was strange to say that someone passed on in such a casual and flip way.

Now that I go out in all weather to milk my goats twice a day, I deeply understand what “kicked the bucket” means in a literal sense. It always seems to be the last goat of the day who will do it, and it’s always once my filled bucket is about to spill over the brim. She’ll kick and slosh her and everyone elses’ milk all over the floor while I hit the roof.

This will happen because she’ll run out of grain, or a fly will land on her wrong, the breeze will imperceptibly change direction, or for no reason at all – and the milk, the bucket, and the last shreds of my patience will all go flying. I now have an appreciation for the murderous frustration that accompanies a bucket full of milk hitting the ground.

I have no idea how it all started, but have a very specific picture in my head.

I imagine a farmer walked into the kitchen after a long day of backbreaking labor. His ornery cow finally toppled the bucket one too many times. He came in just long enough to grab a bag of salt and head back out to the barn. Dinner was getting cold on the table. His wife saw the fury behind his eyes and heard the single shot ring out a few minutes before. “What happened, John?” she asked meekly. “Daisy kicked the bucket,” he replied in a clipped and measured way. They both knew exactly what he meant.

I feel you, Farmer John.

Don’t count your chickens before they hatch

I am the queen of improperly counting pre-hatched chickens. By now, I should know better. After a few years of carefully tweaking the incubator to the perfect environment to optimize our “hatch rate,” I can still be off. My incubator is full of temperature gauges and hydrometers. I have a google calendar solely dedicated to what eggs are in the incubator at any given time.

I “candle” eggs at regular intervals to track embryo development. “Candling” means shining a very bright light through the eggshell while in a dark room to see what’s happening inside. This process used to involve literal candles, but I have a high-lumen led flashlight-like device designed specifically for this purpose.

Even with all that technology, the calendars, the spreadsheets, and modern tools at my disposal, sometimes chicks die. Being born is arduous work, and not everyone makes it. Sometimes they’ll start the process and pip a small breathing hole in their egg and not have the energy to continue. Sometimes they don’t even make it that far. It sucks when you have an egg that you think is about to pop and it just . . . doesn’t.

No matter how much you set up a situation for success, sometimes it won’t come together. Don’t count your chickens, but rejoice in the fuzzy peeping chicks once they’re darting around.

Bleeding like a stuck pig

Woooo, buddy. This one is a “cringe emoji” meets “vomit emoji.” All I’ll say is that this is a phrase for a reason. We all learn things that we wish we could go back and not know.

We had two pigs. One died of natural causes, which was heartbreak in itself. For the other, we hired a “mobile butcher” to come out with his refrigerated truck and handle the slaughter. Kudos to my fantastic neighbor who found a mobile butcher; by the way, I didn’t even know that was a thing.

I’ve hunted birds, and Mark (my husband) has hunted big game for years, but a giant domestic pig was different.

I didn’t name our pig because we knew her purpose was for food when we got her. We referred to her as the “Oreo cookie pig” as she was black and white. When the mobile butcher came out, I gave Oreo cookie pig her favorite grain. My hopes for her were to primarily have a great life, and secondarily, have a quick and painless death, which is why I wanted a professional. Although Oreo cookie pig was very mean, I still cried when the butcher pulled in.

Anyway, suffice it to say, I am so glad to have hired someone who knew what he was doing to handle it. Oreo cookie deserved that. And the phrase “bleeding like a stuck pig” is a thing that people say which is both metaphorically and literally correct. Yikes.

Birds of a feather flock together

I was interested to learn that no matter how they’re raised, “birds of a feather flock together” is an accurate phrase. Last year I had baby ducks, chickens, and guinea fowl that were all raised together. They now share our large bird outbuilding, affectionately named “Big Jim’s Poultry Palace” (after my late Dad.)

All the birds will run around together and sleep in the same building, but it’s funny to watch them out in the pasture. Somehow, even though they all get along fine and grew up together, they know which species they are. They stick with their own kind.

I have no idea what about them evolutionarily makes them know “I am a chicken” or “I am a duck,” but even as I write this and look out the window, the six ducks are all lying in a big pile together while the chickens orbit them, pecking the dirt. They all keeping to their respective species, even when sharing a yard.

Horny as a goat

If 17-year-old boys were an animal, they would be male goats in “rut.” The “rut” is a time during the year, usually fall, where uncastrated male goats get a surge of hormones that make them ready to breed. It’s a kind of a borderline suicidal single-minded maniacal obsession with sex that grips their entire existence.

They get stinky and so incredibly dumb I’m often amazed any goats are still alive on the planet. If you’ve met a male goat in rut you would think they would all have been eaten by predators and none would have been left to perpetuate the species. Of course, I’m surprised most 17-year-old human boys make it out alive, too.

We’ve even had one buck who spectacularly broke his leg trying to jump a fence to get at the girls. He just stood there with his leg jutting out sideways, pretending like nothing happened. Horny goats will ignore barking dogs and sometimes forget to eat or drink they’re so hopped up on hormones.

Every fall in the goat pasture is like a scene out of Night at the Roxbury. It’s any of the cliche 90s or early-2000s clubs named with a single word like “Dazzle,” “Lime,” or “Monarch.” These boys are all ordering bottle service they don’t need and can’t afford, hoping that some young woman will sit with them for a few minutes in exchange for a vodka soda.

Running around like a chicken with its head cut off

It’s such a visual phrase, but so true. Unlike the pig, Mark and I dispatch with our own poultry. Once decapitated, chickens are not in any pain, but their nerves will still twitch. It’s a kind of chaotic jerking that is unnerving (to coin a phrase) but indescribable in any other way. I now fully understand why it became a common saying, there’s nothing quite like it.

Walking on eggshells

Until we moved here, I’d never walked on eggshells. Legos? Sure, ow. Pebbles? Yep. I even once walked across hot coals once at a corporate retreat. That was a dumb idea, and I wonder how they got liability insurance, but I digress.

I grew up with a song about walking on broken glass, many thanks to Annie Lennox. Over the years, I likened situations to walking on eggshells without ever having done it.

That all changed a year ago. I was cooking in our kitchen and heard a goat scream. It wasn’t a “horny like a goat” scream; it was a danger or pain scream. Like human children, there are different kinds of goat yells, and you learn them all.

I flew out the door and threw on the muck boots I keep on the deck. Of course, as I had one and three-year-old boys at the time, random things were often deposited in the bottom of my boots. This time it was the eggshells that had been previously perched at the top of our compost pile.

I knew precisely what it was as soon as I felt the crunch underfoot. Unlike legos or those evil little stabby goat head (also aptly named) stickers, walking on eggshells isn’t immediately painful. If your foot falls correctly, there’s something almost satisfying about the crackle, like breaking that thin ice sheet that covers puddles of water after a snowfall.

Because I threw them on at a dead run, there was no time to pour the eggshells out of my boots amidst the goat screams. Walking, or in my case running, on eggshells is not just stabby stabby stabby, like you would expect. There are two or three footfalls where it doesn’t hurt at all; it just feels crunchy until a shell piece shifts at a right angle and stabs your foot. Even then, it’s a blunt pain, not like a sliver of glass. After three or four stabby steps interspersed with the painless ones, you learn how to step gingerly, almost on the sides of your feet.

What hurts most about running on eggshells is not when they stab you; it’s that you wonder if this will be a step that hurts every time your foot is about to strike the ground. It’s an anticipatory psychological pain.

Weirdly enough, the physical act of walking on eggshells perfectly embodies the idiom in a way I never even considered. It’s that ginger footfall and fear of repercussion that comes with randomized and unpredictable pain. Whoever used the phrase the first time definitely had a toddler fill their boots with eggshells.

The screamer was fine, by the way; he just got his head stuck in a gate. Chalk it up to his irrational horniness, like a goat.